The Top IFR Mistakes: Departing VFR and Canceling IFR

Editor's Note: This article is the second installment in a five-part series by Master CFI/CFII/MEI Gary Reeves, which discusses the most common mistakes he sees good IFR pilots and CFIIs keep making (and how you can avoid them).

Pilots often depart under Visual Flight Rules because they learned in training that it is easier and faster. Sometimes, even air traffic control will ask if a pilot can take off VFR. In most cases, this thinking is antiquated, originating from a time before it was so easy to complete your run-up and get your clearance via your mobile device.

If you are younger than 25 years old, you may not believe that phones were once attached via metal cords to poles outside a fixed-base operator (and even required coins to operate). A pilot would have to call flight service to get a clearance and void time and then run to the airplane and rush to the end of the runway before the clearance expired. My, how times have changed.

The risks of departing VFR

Today, with the relative ease of obtaining an IFR clearance, continuing to depart VFR poses two unnecessary risks.

- You get trapped under a low overcast and cannot get high enough to make radio contact. If you have an issue, much less an incident or accident, ATC may not know you need help.

- You take off and cause a mid-air or near-mid-air collision (NMAC).

The latter happened to me one time in Pennsylvania. I had clearance for an LPV approach to runway 24 at a non-towered field. The weather conditions were overcast at 300 feet, with winds from 240 degrees at 20 knots. New York Center told me there was no observed traffic, and I switched to CTAF.

At 350 feet, I saw a bright white light in front of us, grabbed the flight controls from my student, and jerked the plane up and hard to the right. I felt a hard bump and did an emergency climb. I was sure we had been in a mid-air collision. A minute later, while talking to New York Center, a Bonanza came on the frequency and said, “Bonanza XXXXX, departed XXX runway six, would like to pick up my IFR!”

Yep, you read that right. Departing a class G airport with a 20-knot tailwind into a 300-foot overcast without a clearance (or even making a CTAF call) is totally legal. It also happens to be the easiest way to kill my favorite instructor, me!

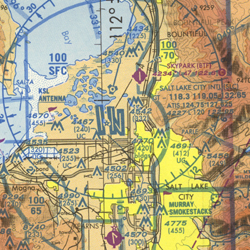

Although there are a few exceptions where ATC will refuse to give clearance for an airplane on the ground, I recommend trying to get it whenever possible before you depart. Airports like KBTF, inside the surface B airspace of KLSC, should serve as a reminder of the complexities that can await VFR departures.

Although there are a few exceptions where ATC will refuse to give clearance for an airplane on the ground, I recommend trying to get it whenever possible before you depart. Airports like KBTF, inside the surface B airspace of KLSC, should serve as a reminder of the complexities that can await VFR departures.

The risks of canceling IFR after departure

Canceling an IFR flight plan in the air before you land is simply less safe. A published instrument approach guarantees you obstacle clearance and that you land at the correct airport, which is easier said than done on a nighttime flight in an unfamiliar area. Even airline pilots are not immune to these challenges. You may remember when a commercial aircraft operated by Southwest Airlines mistakenly landed at a GA airport in 2014.Think of it this way. If you would not turn off the airbags in your car and take off your seatbelt when you are 10 minutes from home, why would you cancel IFR? It disables your safety net.

There is an example in my video series of a very high-time King Air pilot who survived a crash just short of his home airport one night after canceling IFR. The autopsy proves he survived the initial impact. However, trapped in the wreckage, he died from his injuries in the ensuing days because no one knew he was missing.

Even if ATC keeps asking, I seldom cancel IFR in the air unless several pilots are in the pattern at a non-towered airport. In that instance, I know I will need to break off the approach and circle to join the pattern anyway, and with several people on CTAF, they will call for help if I need it.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Articles

.jpg)

The Top IFR Mistakes: Choosing an Approach Too Late

.jpg)

Rising Above the Soup With an IFR to VFR-on-top Clearance