On January 28th, 2020, a Piper Aerostar crashed on approach to Runway 31 at Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport in Springfield, Illinois (KSPI). An ATP-rated pilot, two passengers, and a dog perished in the crash. The pilot reported 5,500 hours of experience in the application for his most recent third-class medical.

The PA60-601P is a pressurized twin with six seats. The specific aircraft in this incident had been modified with dual turbochargers, which boosted engine performance to 350 horsepower (HP) per side. It was a hotrod in the hands of an experienced pilot. Yet, on this particular day, it was a handful during an otherwise benign instrument landing system (ILS) approach.

The Scenario

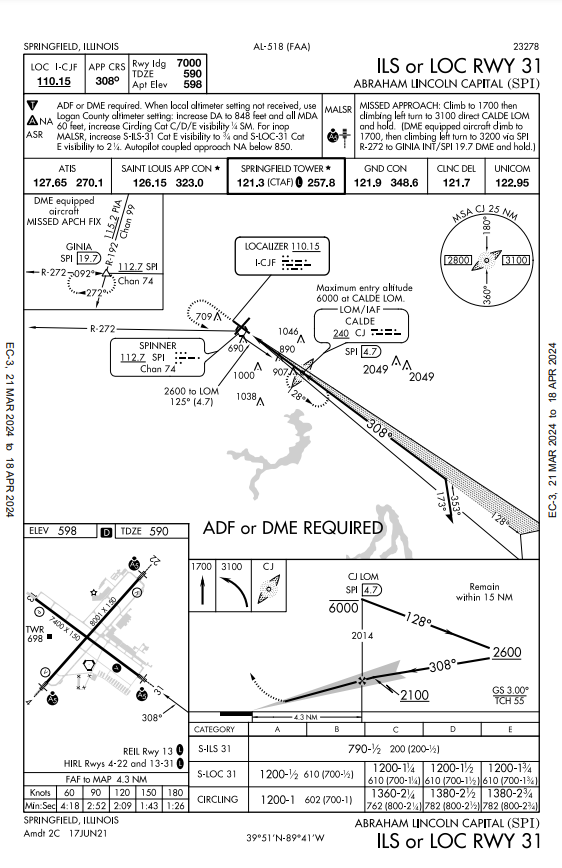

Nothing was amiss as the aircraft was vectored onto the ILS for 31. After the clearance was issued, the pilot made a muddled transmission regarding a navigational issue with the localizer. Air Traffic Control (ATC) stated that the ILS appeared to be functioning and attempted to confirm the frequency with the pilot.

Conveying the information took nearly three tries, as the pilot kept reading back the wrong numbers. The post-crash investigation found that while the memory card for the Garmin 430/530 GPS Navigation/Communications unit expired two years earlier, the ILS 31 frequency in the database was nevertheless correct.

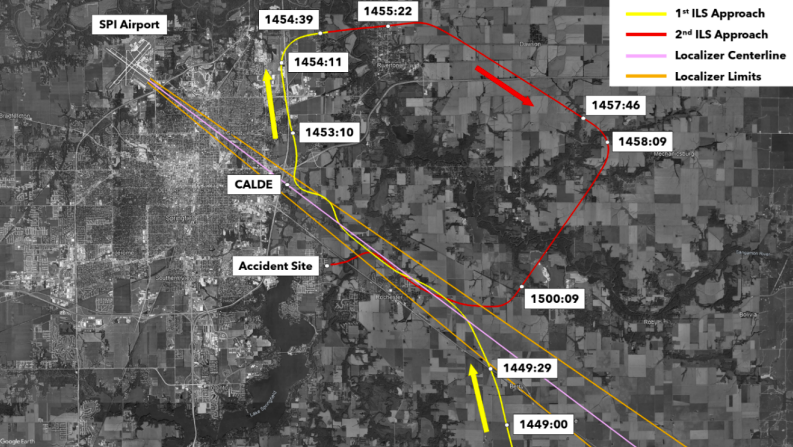

Following the confused exchange between Approach Control and the pilot, the aircraft began a series of S-turns through the localizer centerline. After the series of divergent bracketing maneuvers, Springfield Tower canceled the approach and vectored the Aerostar around for another attempt. ATC had to repeat the vector instructions twice, and the pilot failed to read back the entire clearance both times.

Click the image to enlarge.

Approach Control attempted to get more detail regarding the apparent navigational issue that the Aerostar was experiencing, yet, once again, the radio exchange failed to provide any clarity. The controller offered an Airport Surveillance Radar (ASR) approach instead of the ILS, which the pilot declined. The controller then offered an ILS to another runway, which was a sensible solution if the pilot had been concerned about the ground-based LOC equipment.

Apparently, he was not, instead requesting and obtaining vectors to once again attempt the ILS to 31. The second attempt began with more promise. Though the aircraft settled in a slight parallel to the localizer, the capture was considerably more stable.

This condition continued until the pilot was instructed to contact Tower over the outer marker. Five seconds after this, the Aerostar again diverged from the localizer. 25 seconds after the divergence, the pilot responded to tower inquiries with “We’ve got a prob (unintelligible).”

This was the last communication from the Aerostar.

Analysis

The first thing of note in the ATC transcript is the conspicuous absence of standardized jargon from the 69-year-old pilot of the Aerostar. His communications were rich in slang and deficient in ICAO terminology.

ATC is one of the greatest resources available to an IFR pilot, and the ability to communicate clearly and concisely is a crucial aspect of that communication. The Pilot/Controller Glossary is an important resource with which all pilots should be familiar.

It also was revealed during the post-accident investigation that the pilot had received instruction in the Aerostar five months before the accident. He received a training certificate of completion that was limited to VFR due to a malfunctioning Horizontal Situation Indicator (HSI) onboard the aircraft. Though the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) does not directly comment on it, a malfunctioning HSI fits the difficulty in tracking the localizer that the otherwise experienced pilot demonstrated on the accident flight.

The pilot indicated during his disjointed communication with controllers that he had “neg nav lights on thirty-one.” The PA60-601P comes equipped with a separate VOR receiver, which also can tune the localizer and glideslope for an ILS approach. However, unlike the more user-

friendly HSI, the course needle does not move relative to the aircraft heading. This makes tracking a localizer a much more intensive task.

ADS-B track data with localizer centerline and limits (source: final NTSB report)

Furthermore, the additional unit generally is tuned through a separate nav/radio. This could potentially explain the initial confusion over the localizer frequency.

With all that under consideration, general aviation pilots should take away a few plain lessons.

1. Flying with inoperable equipment is serious business.

There is relief for Part 91 operations in the event that a non-required piece of equipment is inoperative, but it requires specific placarding and (in this particular instance) a maintenance entry. It also requires a preflight evaluation of the impact that the inoperative equipment will have on a particular flight.

The first instrument approaches that I performed years ago were with basic VOR indicators. It can be done, but if you have been using an HSI (and if you have one available why wouldn’t you?) the transition to a basic indicator is bound to be difficult.

2. Structured communication is important.

The fact that the flight school was unwilling to provide an IFR certificate due to the malfunctioning HSI should have indicated to the pilot that the inoperative instrument compromised the ability to safely operate in IMC. A 700 HP twin is a tough aircraft to fly with only basic navigational equipment.

Likewise, the offer from ATC for an ASR approach was an opportunity to accept valuable assistance. In both instances, the pilot disregarded potentially helpful input for unknown reasons.

One of the most elusive skills for many pilots is the ability to take the concerns of others seriously. Early in my career, I flew with a 30,000-hour captain. He looked at me over the drying ink of my temporary certificate and made a comment that has stuck with me to this day: “If something doesn’t look right, be sure to tell me. I’ve been doing this long enough that I don’t have any pride left.”

The details that surround a successful flight are unimportant. All that matters is that you walk away in one piece.

For more information on this flight, you can read the full NTSB report here.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Articles

GA Safety Trends: What Should We Worry About?

4 Lessons in Pilot Proficiency I Learned From My Father

-1.jpg)